Wales has a long history of service to humanity – from revivalist ministers like Evan Roberts (essentially looking for democracy), through fiery politicians like Lloyd-George and Nye Bevan, to committed educationalists such as Maggie’s aunt. In fact, this is so true that it was frequently said that everybody who came out of Wales was either a priest or a teacher. For those who hadn’t met her when she was angry, Maggie was Welsh, and embodied all these qualities: inspiring others through her profound belief in the ability of people to redeem themselves, eloquent in her calls for better treatment of those in her charge, and using education to help young people to understand and address the problems of their world.

Maggie was born into a family that helped others. Her grandfather was a pillar of the National Union of Miners, and a self-taught lawyer who had helped so many people in the community that, as we walked through the streets of the town with him, we were continually stopped by people who wished to shake his hand. Her aunt became a headteacher in London, and her mother worked for the local paper, but took part in many community activities, including running a choir for old people.

Sadly, Maggie’s mother died young, at 36, of cancer. The disease ultimately caused the untimely deaths of many of her relatives, including her grandmother, uncle and the aunt who became her guardian. Her father remarried and there was friction between the young Margaret and her new and, perhaps inevitably, less satisfactory, step-mother. Being Maggie she took steps: although only 12 or 13, she caught the train to London in search of her mother’s sister, Yvonne. Suspecting what had happened, the family phoned ahead and Yvonne was waiting at Paddington to collect her. Maggie now shared her life with a dedicated career headteacher, and when she found it was unlikely she would be able to be a Doctor, her first choice, she duly followed in her guardian’s footsteps.

I first met Maggie in 1969 when, true to character, she had become Vice-President of the Students’ Union at the training college, with responsibility for finding accommodation. I had rooms to let. She came round to vet them, apparently felt I had some potential and eventually moved in.

It was immediately brought home to me that this was somebody who had already formed some views on life: there was no scope for off-hand remarks based on hearsay and prejudice! Be prepared to justify what you say, or get a thorough dressing down!

I found the whole experience totally stimulating. Maggie was like a breath of fresh air in my social life, which at that time alternated between smoky pub lock-ins and noisy dances where conversation was impossible, and violence inevitable. From the start, and throughout our life together, there has been a healthy (although occasionally turbulent) exchange of views, and on any subject.

What I hadn’t realised was that I was a model for what was to follow. From an ill-kempt labourer with little self-esteem she re-worked me into a responsible member of society, holding down a challenging job, and still finding time to do work in the community. This was Maggie’s aspiration for everybody. Her first teaching appointment was at Willesden High. The head at that time was Max Morris, who was also chairman of the Communist Party of Great Britain. The majority of pupils were from immigrant families, mostly from disadvantaged homes. A bit different from teaching practices at Portsmouth High School! Meanwhile, I had moved to Birkenhead, and after a year Maggie got a job in Toxteth, in Liverpool. Again the catchment was very challenging, especially for an outsider (she was referred to as a cockney). She assured me that the Toxteth riots, which broke out later, were entirely coincidental. She got on well with the staff, though, and quickly established herself with a reputation for being able to deal with tough environments.

We moved back to Portsmouth after a couple of years, and Maggie was appointed Head of Science at Portsea Modern, at the age of 25. There is a theme developing here, for when she asked why a lot of car engines were spread along the length of the window-sills in her lab, she was told that it was to protect her from snipers on the balconies of the flats opposite the school. Things were a bit easier after she moved to Kingston Modern but in 1975 Maggie stopped work to have Karl, and subsequently Evan.

The plan was to return to work and use a child-minder, but her children were the most precious things in her life, and after a term she could no longer bear it. She eventually did some part time work by sharing child care with Barbara, whom she had met at Kingston.

Maggie did not return to work full time until Evan started school. This statement is not quite true in that from late ’82 to late ’83 she managed the construction of the house we have lived in ever since.

This was a significant challenge for somebody with no background in building work, but less so to somebody well versed in dealing with the more horny-handed end of humanity. In the year she worked she probably saved 3 times my salary compared to paying an architect to manage the works, and I am confident that she did an infinitely better job.

Maggie joined Crookhorn School and made many friends, including the Deputy Head, Gladys West, who later head-hunted her to Portchester. She was also introduced to skiing, which was an annual event for a group of staff, and became besotted with it, despite being knocked unconscious by a Japanese lady on her first outing. Sadly she later contracted rheumatoid arthritis which prevented her from doing this, but never from working!

Portchester was a turning point in Maggie’s life. The school had a real villagey feel and a very positive attitude to what others might refer to as disability. There, being in a wheelchair was just another personal characteristic like having fair or dark hair, and you were just as likely to find someone in a wheelchair dismissed from the class for bad behaviour as an ‘able-bodied’ person. This equality was so marked that parents bringing children from more protective environments were sometimes shocked to see it, but it was very healthy and appealed to Maggie’s sense of fairness. She moved from the Science department into the learning support area and started to work with those with learning difficulties from whatever cause. The satisfaction she derived from this led her into her ultimate role dealing with the excluded, the vulnerable, the pregnant, the sick and the psychotic and to the most demanding and frustrating but fulfilling part of her life. I will leave one of her colleagues, Eve, to describe this.

Summing up a life in a few words is always going to be inadequate, but it must be done. Early in our relationship Maggie told me that she did not expect to live beyond 38 – in fact she was nearly right: we were together for 38 years, and into these she packed a life of devotion to her family and a fierce determination to get the best out of people and for people. She did not suffer fools gladly, but fought to the death for the vulnerable, disadvantaged and depressed. I and many others like me have benefited from her unconditional love, and we are much the richer for her life.

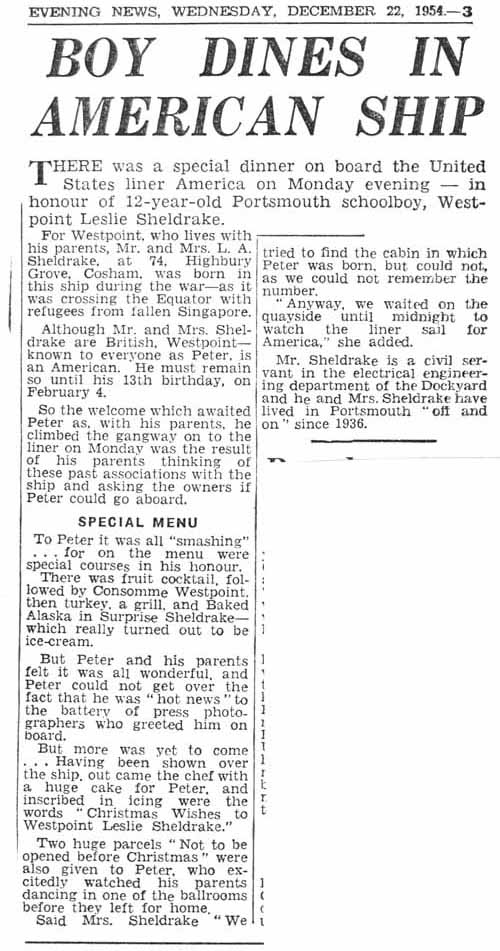

Peter Robert Turnill, third and youngest son of Joan, b 1/5/1947, m 19/10/1971

Peter Robert Turnill, third and youngest son of Joan, b 1/5/1947, m 19/10/1971

Little more than a shed! The picture shows it in 1982 shortly before we demolished it. The house to the left was built by Joan and occupies half the plot they bought in 1952. They had about 2/3 of an acre of ground.

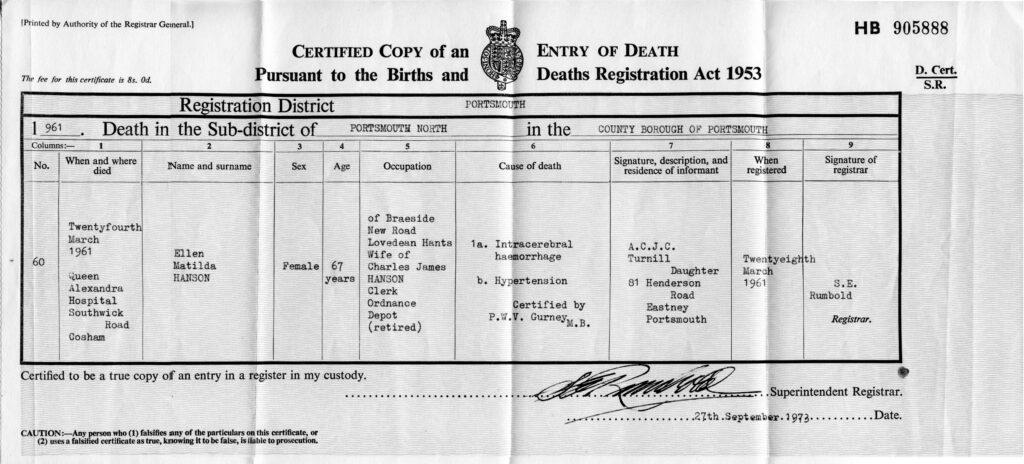

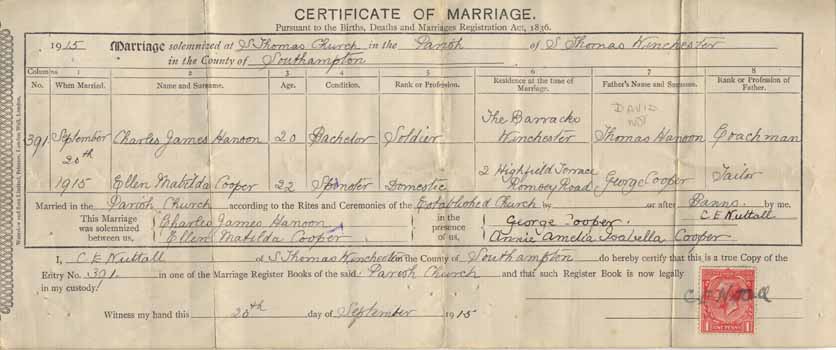

Little more than a shed! The picture shows it in 1982 shortly before we demolished it. The house to the left was built by Joan and occupies half the plot they bought in 1952. They had about 2/3 of an acre of ground. Margaret Ianthe ? ? Hanson, first child of Derwent & Margaret, b ??/??/1942, m ????? d ??/??/2008? Ellen holds Ianthe – taken 1/3/43

Margaret Ianthe ? ? Hanson, first child of Derwent & Margaret, b ??/??/1942, m ????? d ??/??/2008? Ellen holds Ianthe – taken 1/3/43 Richard Brian Turnill, first child of Joan & Victor, b 23/10/1942, d 12/1/1961. Douglas must have got lost somewhere.

Richard Brian Turnill, first child of Joan & Victor, b 23/10/1942, d 12/1/1961. Douglas must have got lost somewhere.

They certainly did …

They certainly did …

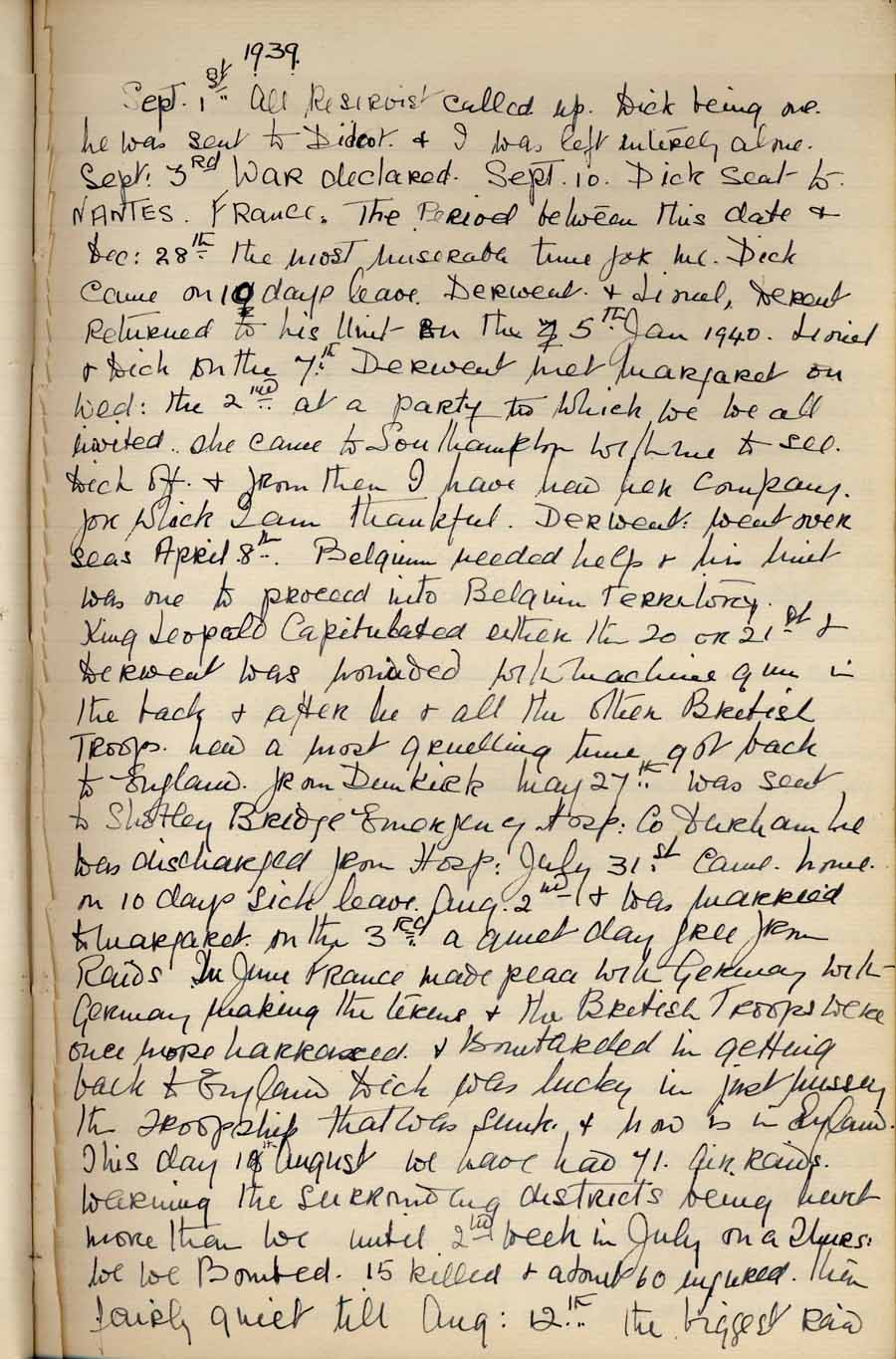

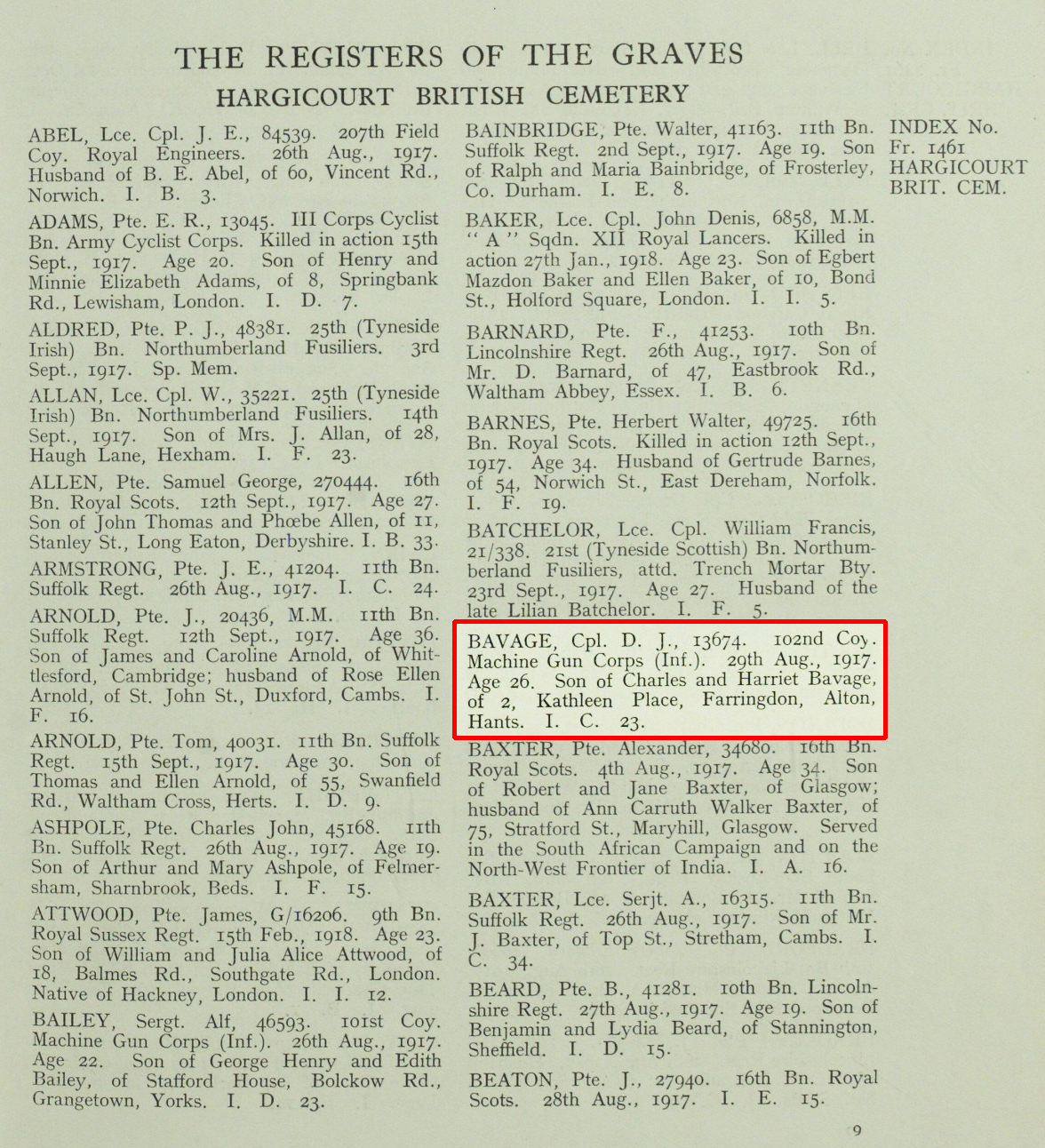

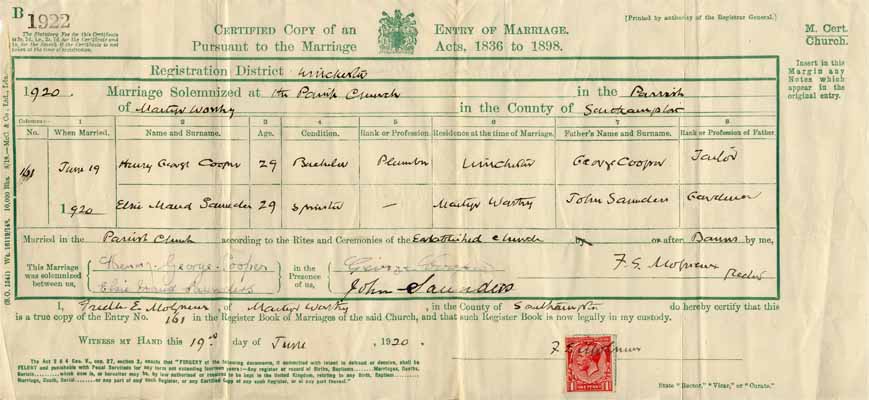

Derwent George Cooper Hanson was their 3rd child, born 8/9/1918, and thus just 21 at the start of the war. Died ??/??/??

Derwent George Cooper Hanson was their 3rd child, born 8/9/1918, and thus just 21 at the start of the war. Died ??/??/??

Margaret Williams, born ??????,

Margaret Williams, born ??????,