No, this isn’t mine. Mine had been leaning against an equally bedraggled B31, against the fence of a house on my way to school. It had been there for some years, and the primary chaincase was lying on the ground underneath it. The clutch had been dismantled at some point and the contents were incomplete and extremely rusty. Although I dropped out of school, the headmaster went to the trouble of finding me a job with a local builders’ merchants. The wages were £7 a week (£6/12s/8d after stoppages). On my way home at the end of my first week I went round and bought it for £5: my mother was not pleased.

The owner told me that it had been used to pull a sidecar and that the extra weight had wrecked the clutch. He had dismantled it to fix it, but never got around to it (sounds a bit familiar). I pushed it round to a friend’s house and installed it in a covered alley there. His mother was most understanding. He owned an AJS 600 on which I’d frequently pillioned. It was only after having my own big bike that I realised it was not normal to slide round corners on your silencers – although it has to be said that the Matchless did this very well, on one occasion around the Wellington Memorial at the bottom of Park Lane. His parents were divorced and he manipulated both to enhance his lifestyle and his pocket. He became a solicitor.

I purchased a second hand clutch from Harry Martin in St. Mary’s road for £1, but the primary chain I recovered by putting this completely rigid loop into paraffin and waggling it for several weeks. It worked, but subsequently snapped when we were practicing riding three up in a side street. This is quite interesting as the person on the tank has to coordinate with the middle person, working the gears. The rear person merely needs to be brave – or is that stupid?

I don’t remember the flashy tank badge. The bike was all black, and the ‘M’ logo was quite small. Of course, I had to ‘tune’ it, and purchased some alloy mudguards (about 30 shillings), some pattern megaphone silencers and, of course, some ‘thruxton’ bars. For those not familiar with this term (they are often called ‘ace’ bars) these were a way of simulating clip-ons on bikes where the upper stanchions were shrouded – as on the production bikes in the ‘Thruxton 500’ race.

At this time I was lodging with a friend’s family and we found a large communal lock-up to keep it in. This had an open yard in the centre, and before I passed my test, we used to go in there and accelerate as hard as we could within the bounds of this area – screeching to a halt at the gates. It can only have been about 20 yards, but the sensation of power was amazing (remember I was riding a 147cc 2 stroke at the time). Unfortunately, the neighbours did not share our enthusiasm.

I don’t recall an all out speed attempt on this bike, but I have a strong recollection of the satisfaction I felt the first time I saw the needle go past 80mph. I think the experience was enhanced by the sidecar gearing, making it seem much more lively than it was, but I later found the gear ratios themselves were well chosen.

This was quite an educational period, as I learned about electricity, why it’s best to have good lights, and the cornering capability of Minis. I learnt about high voltage electricity and rain while riding between Copnor Bridge and the Prison in Portsmouth one day in a torrential downpour. Suddenly the bike went onto one cylinder, and, looking down, I could see that the left hand plug cap had jumped off . . . you’ve guessed it. Reaching down I grasped the offending item and got about 20,000 volts through my soaked gloves – yikes! Reviewing my decision, I decided to pull over and stop the magneto before my next try. While the magneto had proved itself very effective, the dynamo / control box set up was less so. Eventually I removed the dynamo (I’m not sure why – I probably took it to pieces and lost them) and, faced with a large circular hole in the timing chest, spewing oil under the bike, and using a bit of lateral thinking, I araldited a suitably sized rubber ball into the hole. All I needed then was a good battery, regularly recharged and everything was fine.

“A good battery, regularly recharged . . .” – well, of course this didn’t happen, and I was frequently short of light and horn power. It was at just such a time that the friend, whose family had taken me in, asked for a lift to his part time work (delivery boy for an off-licence). He had to be there for 6pm, and it was January – getting dark. The shop was at the junction of Francis Avenue and Albert Road in Portsmouth. Francis avenue is a long straightish side road, with many more minor streets crossing it. My friend was late, so I did not spare the Matchy’s 28 or so horses, and was doing about 65 when I spotted a bubble car approaching, indicating right. It was one of those with the door at the front (Isetta?) and two large tubular crash bars as bumpers.

The poor devil didn’t stand a chance. A black bike ridden by a man in black (a ‘trialmaster’ jacket) with, at best, a pale glimmer in its headlamp, approaching at more than twice the legal limit. Nope, he turned. I felt the bang, but we stayed on and I was able to pull into the kerb, where my friend jumped off, and I laid the bike down on my ‘good’ side. He was now jumping about on his left leg, holding his right leg and shouting “you’ve broken my bloody leg!”, etc.. Of course, I hadn’t, but looking down, I could see that my calf now had a new 90º bend in it and my toes were now pointing upwards. Not too good, but better than if my leg had slipped into the loop of his crash bar . . .

People came out, found me a blanket, but fortunately didn’t try to move me or the bike. From my recollection, I was there for about 40 minutes before the ambulance arrived, and I remember feeling battery acid dripping onto my good leg, but not doing anything about it. The ‘neighbours’ plied me with cigarettes to pass the time (I could probably sue now). The ambulance men picked me up and put me in the back without any splinting and as we drove to the hospital over the rough Pompey roads the loose end of my leg was bouncing up and down on the stretcher. I must have been in shock, because I don’t remember so much the pain as the revulsion in looking at it. I eventually raised the matter with my carer, and he had the good grace to hold it down for the remainder of the journey.

Waiting in casualty (so what’s new?) my shock must have worn off, because I remember hearing a nurse mention analgesic and this prompted me to suggest that this would be a good idea for me, as my leg hurt, a bit. “Of course it hurts”, she replied in a strong Irish accent: “You’ve broken it!”. I was surprised to be fitted with wooden splints, and sent home. Luckily my friend’s mum took everything in her stride and sorted me out in the front room with a bucket. A policeman came round to take a statement, but happily he must have thought I’d been punished enough, as he told me “I’ve ridden your hot rod back to the station” and did not pursue how fast I had been going. I heard no more about it, but, as an invalid, was forced to return to my mother’s house.

I enjoyed ‘street racing’ – doing ridiculous speeds around the town and enjoying the tremendous bursts of excitement, although these were often succeeded by black depression when the adrenalin rush had receded (Is this where the post-coital triste came from? Answers on a postcard, please!). On one occasion I was chasing a Mini down a fairly rural and swervy road when I came to one of those bends that keep tightening up. Most cars in those days were pretty vertical and rolled so much that any corner demanded respect, but this Mini barely slackened its speed. I was determined to stay with him, but was conscious I was still on the heavily worn sidecar type tyre that the bike had come with, and, although we made it, I was much more circumspect when following Minis in the future. I must have been a fairly sensible kid, though, because after a few months of this sort of behaviour I appear to have refitted the normal handlebars. This may have been because I was now working in London and using the bike to come home at weekends.

I was living in a hostel off Sloane Square (£3.14s.0d a week for a bed in a dormitory, breakfast and evening meal) and commuted to an office by Lambeth Bridge. The bike was ideal for this, but really came into its own the night a ship hit Vauxhall Bridge and closed it. Even in those days London traffic was at a critical point in the rush hour. Removing one link, when they closed the bridge, brought on meltdown. Everything stopped. I got home by riding on the pavement.

On £8 a week, petrol money was tight, and I would often hitch-hike home at weekends, riding the bike to Roehampton Common (at the top of Putney Hill) and parking it in a side street to await my return. On a Friday then, I would be riding dressed in a suit and sitting on my umbrella. Shortly after leaving work, I was riding along the embankment when I was pulled over by a motorbike cop (why did we always call them ‘speedcops’?). By then, the bike was looking a little worse for wear – fairly rusty despite the oil leaks, the seat cover was badly ripped, there was the rubber ball in the timing cover, etc., etc.. The policeman started to check things – tyres (just about legal), brakes (OK for their day), lights and horn (phew, just enough left in the battery, he got on it and rocked the forks (still OK!). Eventually he was forced to the conclusion that it was scruffy, but all there (sounds like my motto!). He looked at me and my umbrella: “You ought to find some other way of carrying that or you’ll damage you marriage tackle” he said. I thanked him for concern, and rode off.

On another occasion I was riding up Putney Hill and got too close to an old chap wobbling about on a push-bike. The end of my handlebar caught his sleeve, and he fell off. I stopped and apologised, and despite his protests took him to a police station and reported the incident (I think I remembered it was an offence not to report an accident where somebody was injured – he had a few cuts and bruises). Happily he didn’t wish to pursue it and the copper didn’t want the paperwork, so nothing came of it. I have to confess that about 25 years later I did a similar thing, knocking off a motorcyclist with my caravan. This time I accepted the rider’s protests and the incident went unreported – I think they (justifiably) would have thrown the book at me.

The bike did some good journeys and I well remember the first time I enjoyed the sensation of ‘bend-swinging’. This seems to come on after a prolonged session where you are able to develop a rhythm through sets of bends. It must be almost unheard of now (in England at least) because there is always some other vehicle in the way. This was on the way to Brighton, where that year’s Motorcycle Show was held. On another occasion, myself and a friend from the Hostel went to Brands Hatch for the day, where Mike Hailwood, Phil Read, Bill Ivy and the Boddices (père et fils) were performing. It was a good day, and one I remember well, but it struck me how little of the race you could see. We started at Hawthorns (noting how Hailwood looked ‘slow’ – i.e. not ‘scratching’ – although in the lead), moved up to Druids, went round to Dingle Dell (watching the much hyped Read and Ivy tussle through here was thrilling) and so forth, but it was hard to see the whole picture. We were able to go into the paddock and I remember liking the Boddice’s transporter – an old motor coach with a ramp at the back for the outfits and accommodation up front). It would be more than 40 years before went to my next motor race.

I can’t remember what became of the bike. I do recall that I stripped the engine down (I’ve still got the timing wheel pullers, etc.) and I suspect it was never rebuilt. It was still around when I bought my next bike and was retired to the front garden while I honed my mechanical skill on G9 #2.

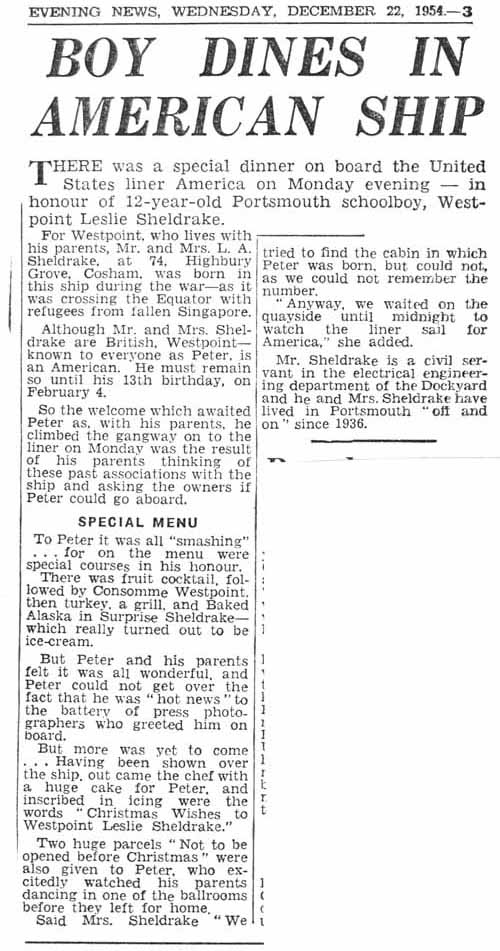

Peter Robert Turnill, third and youngest son of Joan, b 1/5/1947, m 19/10/1971

Peter Robert Turnill, third and youngest son of Joan, b 1/5/1947, m 19/10/1971

Little more than a shed! The picture shows it in 1982 shortly before we demolished it. The house to the left was built by Joan and occupies half the plot they bought in 1952. They had about 2/3 of an acre of ground.

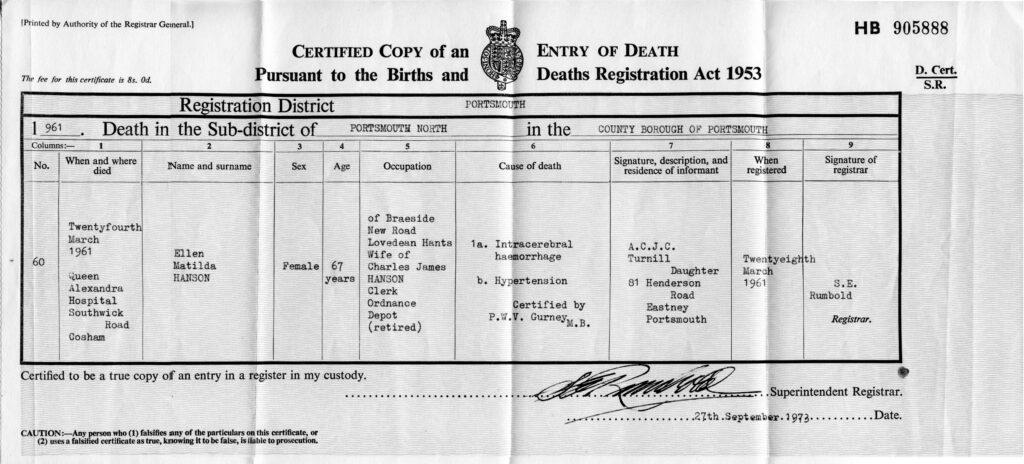

Little more than a shed! The picture shows it in 1982 shortly before we demolished it. The house to the left was built by Joan and occupies half the plot they bought in 1952. They had about 2/3 of an acre of ground. Margaret Ianthe ? ? Hanson, first child of Derwent & Margaret, b ??/??/1942, m ????? d ??/??/2008? Ellen holds Ianthe – taken 1/3/43

Margaret Ianthe ? ? Hanson, first child of Derwent & Margaret, b ??/??/1942, m ????? d ??/??/2008? Ellen holds Ianthe – taken 1/3/43 Richard Brian Turnill, first child of Joan & Victor, b 23/10/1942, d 12/1/1961. Douglas must have got lost somewhere.

Richard Brian Turnill, first child of Joan & Victor, b 23/10/1942, d 12/1/1961. Douglas must have got lost somewhere.

They certainly did …

They certainly did …

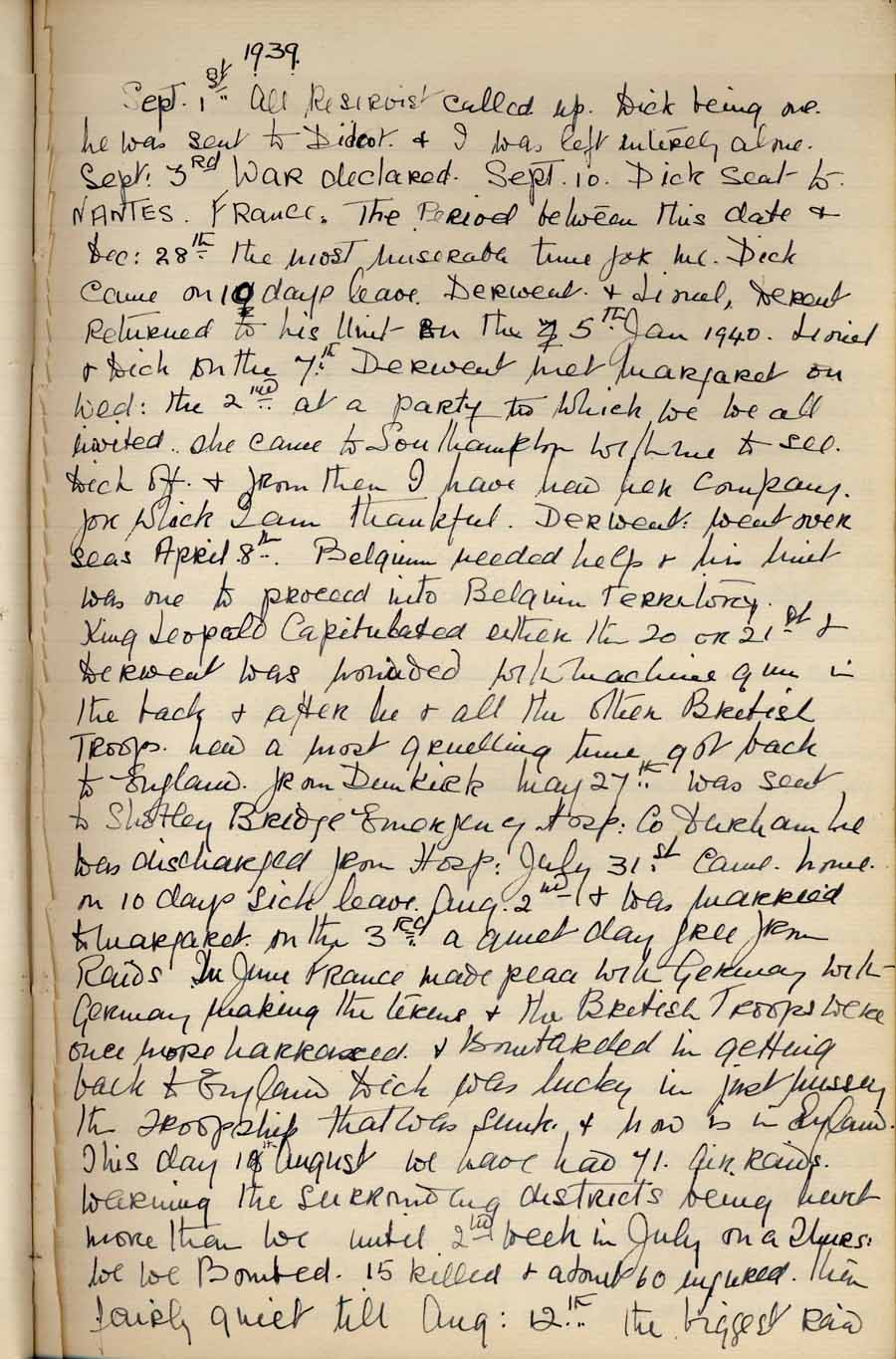

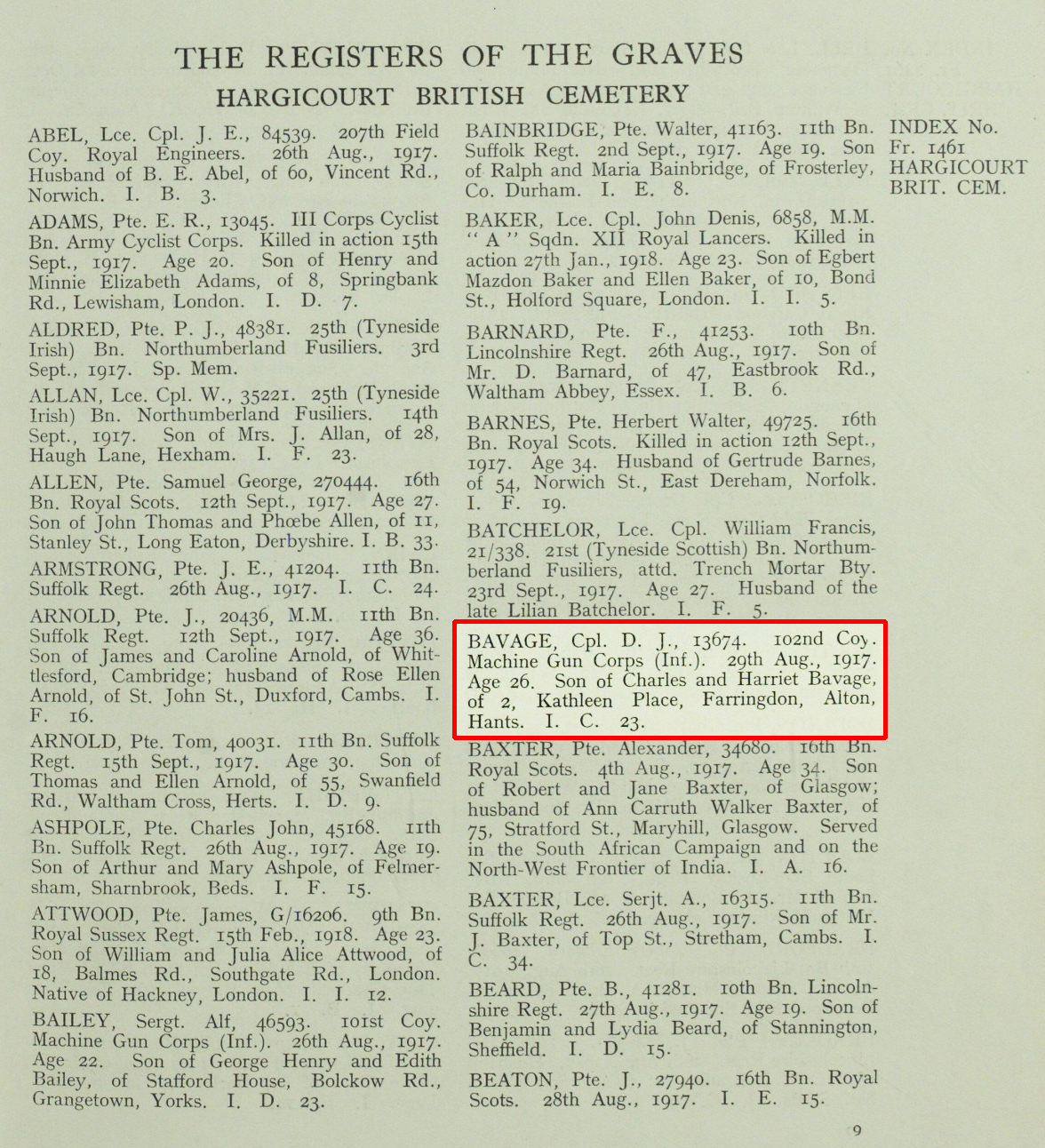

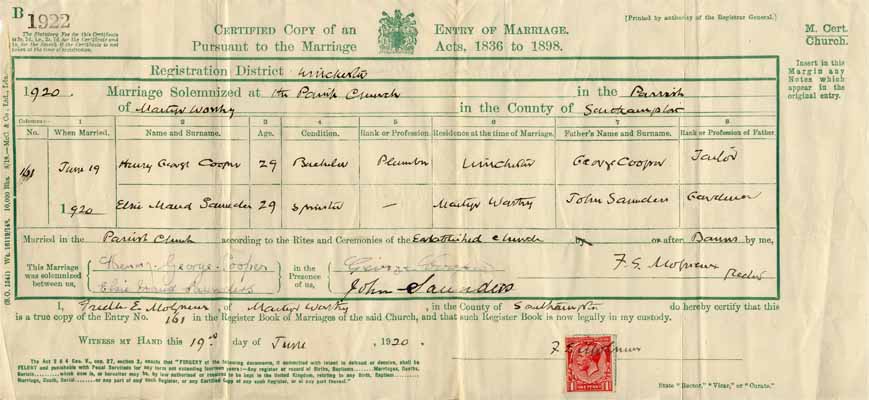

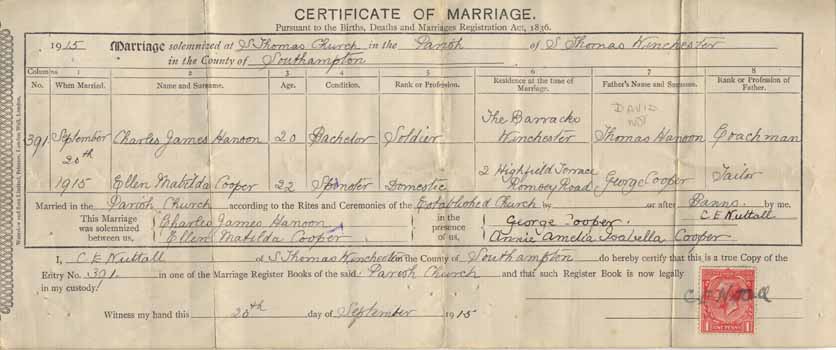

Derwent George Cooper Hanson was their 3rd child, born 8/9/1918, and thus just 21 at the start of the war. Died ??/??/??

Derwent George Cooper Hanson was their 3rd child, born 8/9/1918, and thus just 21 at the start of the war. Died ??/??/??

Margaret Williams, born ??????,

Margaret Williams, born ??????,